A Wilde Night: Oscar (The Australian Ballet) Review

The Australian Ballet premieres a new ballet of the life and works of Oscar Wilde, its first new full-length commission in over two decades

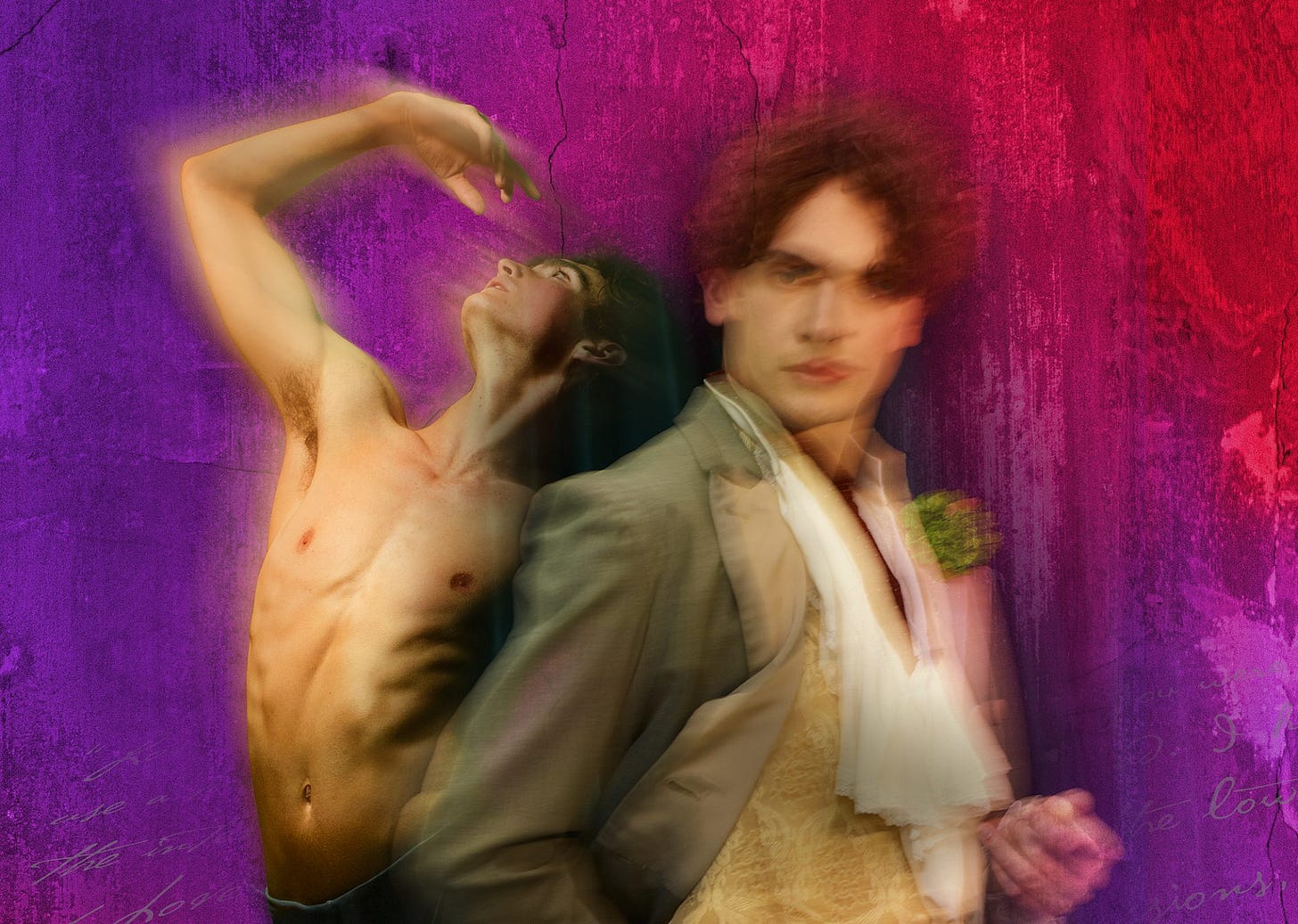

The Australian Ballet’s Oscar, which premiered last night at Melbourne’s Regent Theatre, marks a daring departure from traditional ballet narratives, embracing a full-scale biographical work centred on the iconic Oscar Wilde. Choreographed by Christopher Wheeldon, this ballet presents Wilde’s tumultuous life, offering a rich tapestry of historical figures, literary references, and poignant reflections on queer identity in a genre that has traditionally favoured heteronormative themes.

Artistic Director David Hallberg introduced Oscar as a reflection of the Australian Ballet’s commitment to diverse and inclusive storytelling. In the historically conservative world of classical ballet, Oscar represents a significant leap forward, offering a complex portrait of Wilde as both a celebrated artist and a persecuted queer man. Yet, despite its groundbreaking nature, Oscar treads familiar artistic ground for Wheeldon, whose earlier work Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was also featured in this year’s Melbourne season. The sonic and choreographic similarities between the two works raise questions about repetition, with Oscar sometimes feeling recycled rather than a bold new start.

The ballet opens with Wilde’s imprisonment for “gross indecency,” using spoken narration to set the tone for a work that skilfully intertwines Wilde’s personal history with elements from his stories. Callum Linnane’s portrayal of Wilde is a masterclass in balancing flamboyance with vulnerability. His performance captures Wilde’s wit and charm in the early scenes, but as Wilde’s life unravels, Linnane’s portrayal becomes brittle and fractured, reflecting the writer’s internal collapse.

The first act, however, struggles musically. Joby Talbot’s lush score, while undeniably beautiful, echoes his earlier work in Alice, lacking a distinct musical identity for Wilde. The absence of a clear leitmotif to anchor the character detracts from the narrative’s emotional depth. However, the shift into London’s underground queer scene brings a welcome burst of energy, both musically and choreographically. The "music hall dames" dance, performed by Marcus Morelli and Cameron Holmes, stands out as one of the night’s most joyous moments. Their near-can-can-esque frocked performance evoked the performance’s largest applause, for a scene celebrating Wilde’s immersion in a vibrant but dangerous world of queer nightlife.

The inclusion of The Nightingale and the Rose within the first act’s narrative, while visually striking, struggles to establish a strong thematic connection to Wilde’s life. Ako Kondo’s exquisite, bird-like movements as the Nightingale are haunting, yet the allegorical parallels between the fable’s tale of self-sacrifice and Wilde’s journey feel underdeveloped. The soprano voice of Victoria Lambourn, however, adds a supernatural quality that deepens the emotional impact of the scene, especially during the tragic climax.

Act Two finds its footing more firmly. Opening with the stark image of the prison curtain marked with the days Wilde has spent behind bars, the act delves into the complexities of Wilde’s relationship with Lord Alfred Douglas, or Bosie. Benjamin Garrett’s portrayal of Bosie is delicate and nuanced, and his chemistry with Linnane in their grand pas de deux is palpable. This intimate duet, filled with sweeping lifts and tender moments, stands as one of the ballet’s most visually arresting sequences, capturing both the passion and peril of Wilde’s love life.

The integration of The Picture of Dorian Gray into this act is more successful. Adam Elmes, as Dorian, brings an eerie charisma to the role, and the scenes from Wilde’s novella serve as a mirror to the writer’s own descent into infamy. Particularly effective is the moment where Wilde stands in the frame of Dorian’s portrait, symbolising the intertwining of his art and his personal ruin. Talbot’s score, which leans more heavily into percussive and electronic elements in this act, heightens the tension and drives the narrative toward its inevitable tragic conclusion.

The ballet’s final scenes, depicting Wilde’s release from prison and his exile to Paris, are heartbreakingly raw. The narrator’s reminder of Wilde’s untimely death just four years after his release serves as a poignant commentary on the cost of living one’s truth in a repressive society. Linnane’s final moments on stage, as a broken and defeated Wilde, leave a lasting emotional impression.

Visually, Jean-Marc Puissant’s set design is both grand and relatively static. While the classical façade wrapping the stage creates an impressive visual, the limited use of projection mapping often feels washed out by the lighting, preventing the set from fully transforming Wilde’s memories into the mystical worlds they represent. However, the blood moon projection at the end of Act One, dripping with red to create the rose in The Nightingale and the Rose, is one of the more successful uses of this technique.

Costume design, on the other hand, is one of Oscar’s triumphs. The opulence of the early scenes, with Wilde draped in luxurious fabrics during his rise to fame, contrasts sharply with the stark prison garb of the later acts, visually emphasising Wilde’s fall from grace. The contrast adds depth to the narrative, highlighting the shift from Wilde’s public persona to his private suffering.

Overall, Oscar is a bold and exciting addition to the Australian Ballet’s repertoire. While not without its imperfections, it succeeds in pushing the boundaries of ballet, offering a queer narrative that feels both intensely personal and universally resonant. Wheeldon’s choreography, paired with Talbot’s evocative score and stunning performances from the cast, ensures that Oscar will leave a lasting impression. As Wilde himself once wrote, “The truth is rarely pure and never simple”—and Oscar is a testament to that complexity.